Jews were nowhere and everywhere in early modern England. The depictions of Jews in well-known Elizabethan plays like William Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice and Christopher Marlowe’s The Jew of Malta coincided with a centuries-long expulsion of the Jews from England (ca. 1290–1656). It is unlikely that England was ever fully without Jews, however, and after the expulsions from Spain (1492) and Portugal (1496) a number of crypto-Jewish communities established themselves throughout the country.

Little is recorded about most of the individuals from these communities, with a few notable exceptions—most remarkably Roderigo Lopez, a converso who was convicted of plotting to poison Queen Elizabeth in 1594. Given so few Jewish people in sight, what social conditions and spores in the cultural imagination gave rise to characters like Shylock and Barabas?

During my Artist Fellowship at the Folger Shakespeare Library (September 2024–January 2025) I asked questions like: From what remains, what can be understood about the lives and experiences of the Jews living in a country that defined its identity, to a certain extent, by their absence? How do works like Merchant of Venice and Jew of Malta sit at the intersection between art and the social, between the imagined and the real? To what, and for whose, purposes were characters like Shylock and Barabas put?

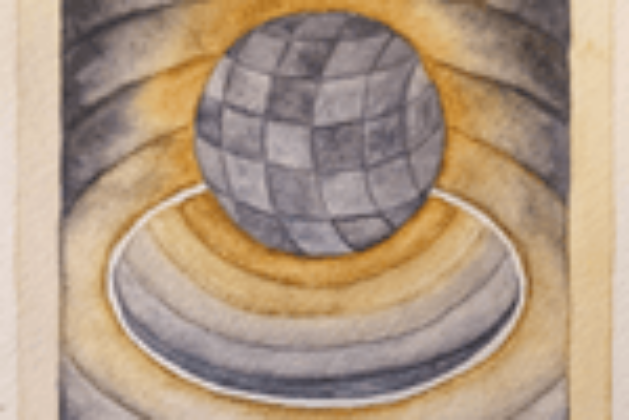

Before my arrival, I planned to make a series of textile artworks in response to these questions. During my fellowship, I decided these works would specifically take the form of quilts. The medium, to me, felt like the right visual language to bear the expansive weight of these histories.

Leave a comment